As if war, environmental problems and rising inflation aren’t enough, we are also looking at a new widespread disenchantment with classic profit driven capitalism and disillusionment with the workplace. I prefer to refer to times like these as what Gershom Sholem once called the “plastic hour” – those crucial moments when it is possible to act, where everything can change because history is in a volatile flux.

So how do we act, and where and who do we go in times like these? The writer Robert Frost once said, home is the place where, when you go there, they have to take you in. Indeed one of our first reflexes as humans is to hunker down in our homes. Think of the trend to cocooning in the Cold War 1980s and more recently the Hygge trend as a narrative lifestyle choice during the pandemic. Just as we need to adapt in order to grow and flourish in times of crisis or change, our homes cannot be neglected if we are to live well in them. Today we are looking to the future with a new relationship to our homes – what I call the trend to Home Suite Home. This is the result of finding new purpose, investing more thought, time, energy, money and love in where we live. It is about an upgrade from simply being a “home sweet home”, to “home SUITE home” (like the joy of an upgrade in a hotel from a room to a suite).

The shift in our relationship to our home, and the upgrade, was partly thanks to covid. We tidied up thanks to reading or watching Marie Kondo, adapted our floorspace to accommodate a home office, and even welcomed a Spathroom (spa + bathroom) a place we could retreat to and treat ourselves. Even the kitchen evolved to our new needs and became more “conscious” , i.e embracing new cooking skills and awareness of ingredients and food waste. For many today our homes are now better adapted to embrace the fact that we have moved from a lifestyle of work life balance to a state of “work-life blending”. We need to remember that our homes are in many ways just like us, the inhabitants. They are a complex adaptive system that in order to evolve must constantly adapt to new circumstances. As the writer Stewart Brand once said, “Age plus adaptivity is what makes a building come to be loved. The building learns from its occupants, and they learn from it.” Put simply, as the world and your life adapts, so too does your home.

Beyond the design upgrade to a suite, how do our homes sustain us socially in a crisis? How do they nurture the need for what sociologist Jeffrey Hall calls our social biome, our personal ecosystem of relationships and interactions that shape our emotional, psychological, and physical health.

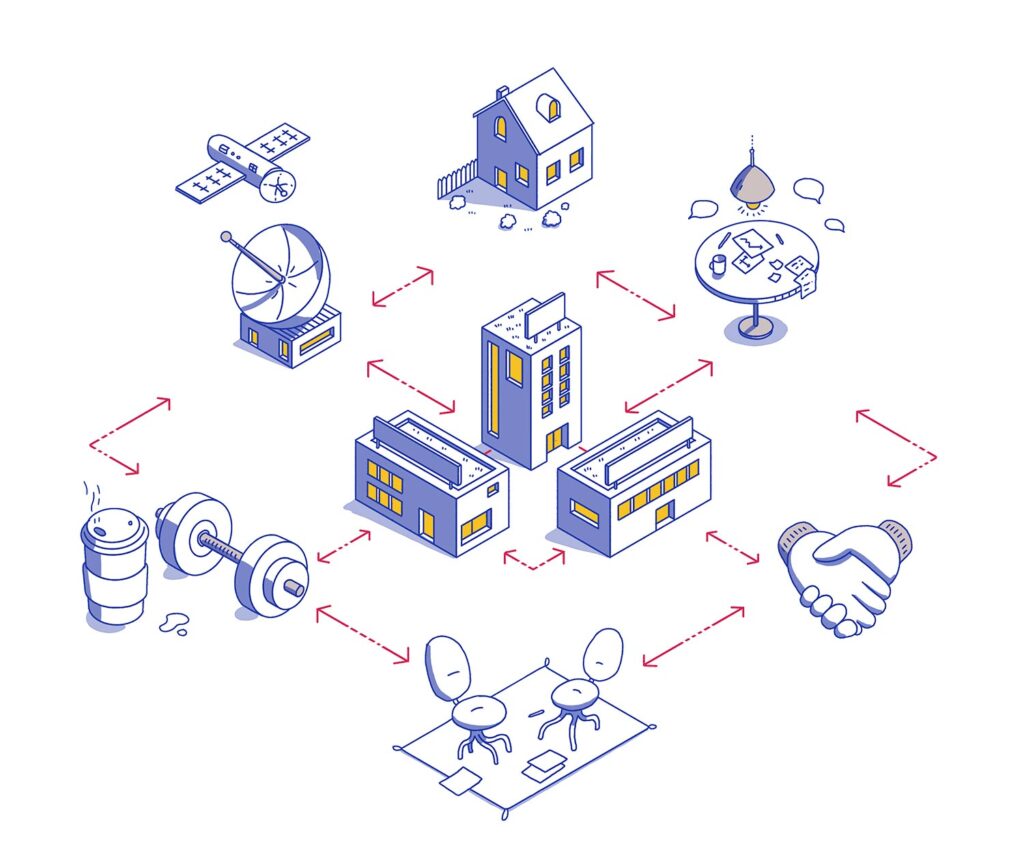

Covid taught us the importance of community – we had to be deprived of it in order to know how important it is. But still we are living in an individualistic society with high levels of mobility and single households. Loneliness is a real problem for our mental and physical health – hanging over our society like a thick smog. Another reason is that a few generations ago we were typically born into a community and had to find and fight for our individuality. Today things have turned around and we are born as individuals and have to find our community – hence the trend to vertical villages, villageisation in town planning, and the rise of individualistic communities, also known as intentional communities. And while the notion of an individualistic community sounds like a contradiction in terms, it is in fact a synthesis – the result of the result of a trend/countertrend dynamic. They are places where we can live and function as individuals, but with the support of a community.

One of my favourite examples of such a community is the SällBo residential project in Helsingborg, Sweden. It is a bold example of co-living — a multicultural, multigenerational project with fifty one apartments, aimed at combatting loneliness. A former retirement home, it has been revamped to include lots of shared spaces for everything from cooking to arts and crafts to exercise and games. What makes it especially interesting (and unique) is that there are some very unusual clauses in the rental contract. First, you can live there only if you’re either under the age of twenty five or a pensioner. Second, you must socialise with the other residents for at least two hours per week. If you don’t, you have to move out. One resident, Gunnel, told the BBC that before living there she had a very comfortable life, “but it was so lonely. There were days when I didn’t speak to anybody, and you get a bit odd.” Twenty year old Fia has become a fixed friend to Gunnel, who is eighty six, and admitted that before living there she was also lonely and depressed – working for eight hours, going home, eating alone, and playing computer games. Fia now helps Gunnel with her computer, and Gunnel has taught Fia a lot about life. Not only has the project transformed the residents’ lives, but the organisers believe that in the long run it will also result in economic savings, because the residents are happier and thus will be less sick and reduce the costs of health care. As Rob Hopkins wrote, “If we wait for governments, it will be too late, If we act as individuals, it will be too little, but if we act as communities, it might just be enough, and it might just be in time.”

By Oona Horx Strathern

- Rob Hopkins, From What Is to What If: Unleashing the Power of Imagination to Create the Future We Want

- Maddy Bowen, “How the Swedes Are Tackling Loneliness,” filmed and edited by Benoit Derrier, BBC Crossing Divides series, February 26, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/reel/video/p083q0gz/how-the-swedes-are-tackling -loneliness.