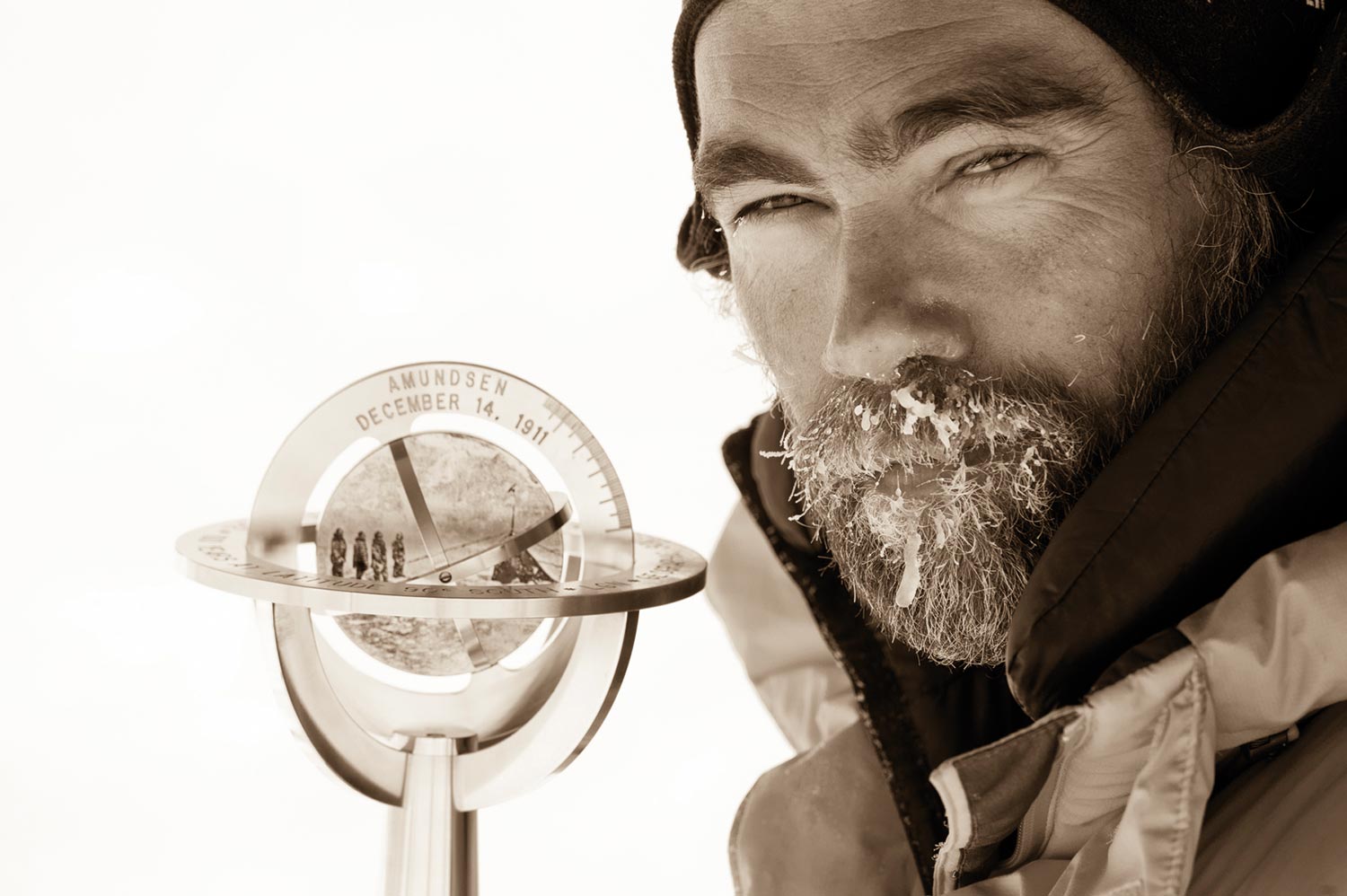

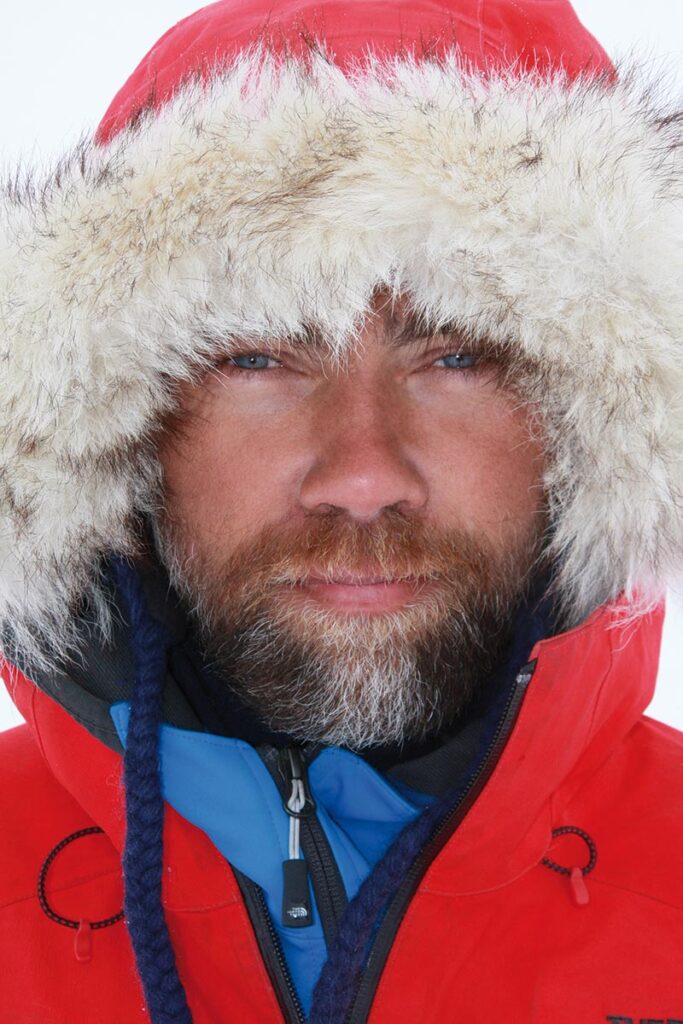

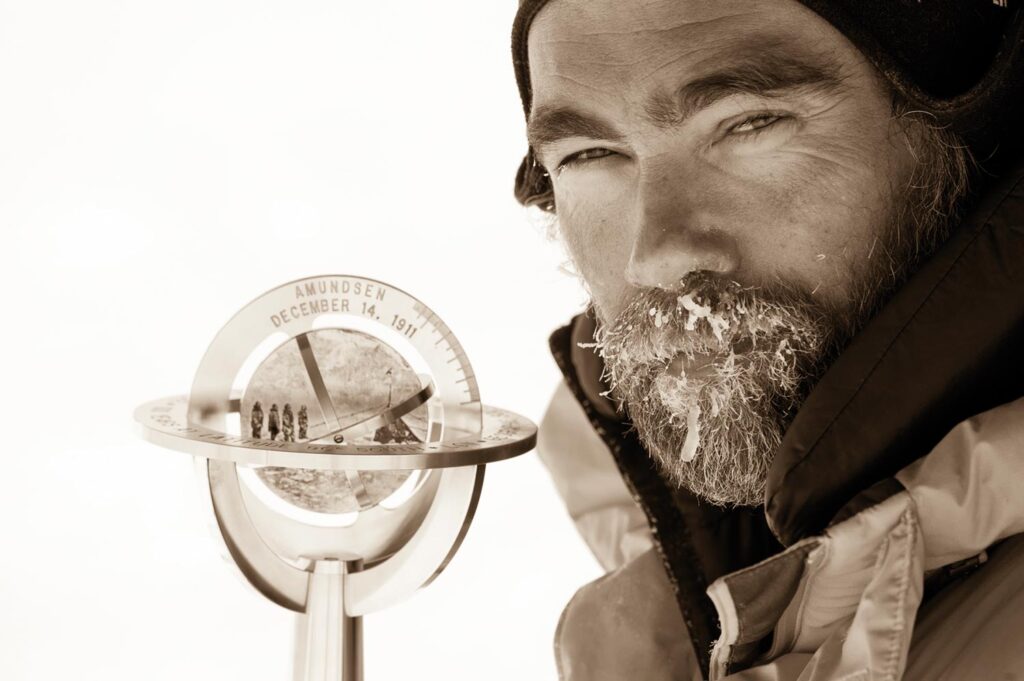

Since that trip to the Sahara, he has been traveling the world, focusing on the overlooked issues. Meanwhile Johan Ernst Nilson has undertaken an impressive 62 expeditions to 182 countries, spending over 3000 nights in a tent. He describes himself as an explorer, philanthropist, and adventure activist.

Johan was an early advocate for climate change, even before Al Gore’s documentary brought it to widespread attention. He documents all the things that are terribly wrong on our planet: endangered animal species, disappearing indigenous tribes, and the risk of losing valuable wisdom along with them. Aside from artificial intelligence, the prospect of losing ancestral wisdom is a matter that deeply concerns him.

In this remarkable conversation, you’ll meet a truly inspiring human being who is determined to change the world together with us to re-connect with our most valuable source of wisdom on this planet: Mother Nature.

Interview by Sandra-Stella Triebl

Assisted by Sara Almeida Rodrigues

Ladies Drive: What is the scent of your childhood?

Johan Ernst Nilson: My memory of my childhood in Sweden was nature. And the reason for that was that I spent my summers out in a summer house with my parents, and I was always down fishing by myself and walking around in the forest. So I would say the smell of fresh grass, trees, freshwater and fish.

Can you share a little bit how you grew up? What influenced you as a kid and as a teenager?

Well, when I grew up, I was a little bit confused. I wanted to try everything. So I tried a lot of things. I was a piano player for many years. I was working in bars and restaurants all over the world and was living in South of France for instance. And then one day when I was around maybe 20 something, I was sitting in the Grand Hotel in Stockholm playing the piano and had a conversation that would change my life – due to a bet with a friend. He provoked me if I, who had the lowest grades in gymnastics as a teenager, could bike from Sweden to the Sahara. Well…challenge accepted!

The week after I quit my job, bought a bicycle, a tent, and then started biking to the Sahara. The first day, I threw up. It was the worst thing I’ve done in my entire life! So I called my mother and said: “Mum, I’m coming home. This was not fun.” – “Yeah, but my son, you are doing so good, what you did today, that was so impressive. You know, you were biking for many hours today. If you do the same thing tomorrow, you think you could do that?” – “Yeah, but then I’m coming home.” So, I called my Mum the next day. “Okay, I did it again. But now, now I’m coming home. This is not fun.” – “Yeah, but you did it yesterday, right? And you did it again today. If you do the same thing tomorrow, well, you see where this is going. So if you do only today, for 52 days, you get to the Sahara.” And imagine – I made it! When I arrived in the Sahara, I was sitting there with sand between my toes and thought like: “Damn, did I just bicycle to the Sahara? No, no, no, no, no. That’s impossible!” But you know what I did? Every day I went a little bit more south. If you do that, eventually you get to the Sahara. The thing is, not seeing it as a long-term problem, but as a short-term solution. So every time I had a little bit of a problem, I was saying that: “Yeah, but I’m just doing that two more hours. I can do that.” But if I see the long stretch to the Sahara from Sweden, you will give up directly. If I’m thinking about it now, I’m in the South of France, I’m going to bike to the Sahara, even now 30 years later, oh that seems like a long trip. But if I say: “I’m going to go from here to the next village, yeah, I can do that.” So then the year after I thought, if I could bicycle, maybe I could do it with the sea kayak. So I took a sea kayak and I started to kayak and did the same thing, that took longer to go for six months to kayak, 10 hours per day from Stockholm to the Sahara in a kayak. And then it continued, more and more.

From being a piano player, I started to do movies, I went to film school, I went to journalism school, I started to write. Because I needed to document what I was seeing. Because it was so important to see everything for myself. And I was coming home to my Mum and my Dad and saying: “I experienced this. Like in 1995, I walked across Alaska and I just had to share it with others” – So I started to take photos, more and more. Then I started to do photo exhibitions, photo books and I wrote my first book in 1991, and then just continued more and more and more. The first book that I wrote was 365 poems. It was a poetry book (laughing). So when doing my adventures, I started more to be artistic in a way of documenting my adventures, because I felt that this is something people need to see. Tribes disappearing, beautiful nature, glaciers disappearing, all these things. We need to talk about this! I felt like after a while, it’s my responsibility to document it. It’s not even like that I want to, I feel like I have to. So 1997, I spent four months in the Antarctica documenting and doing the first movie about climate change. And at that time, nobody wanted to see it (laughing). I had like 0.1 viewers because everybody was like saying that: “Oh, it’s getting warmer. Great news!” – “No, no, no, no, no, no, that’s not good! It’s bad news!” – “That cannot be bad news.” And then I started to explain. “That’s bullshit. If that was true, everybody would talk about it.” Ten years later, Al Gore made his movie about climate change, and then it took off a little bit more. But you needed a person like that for it to take off. That doesn’t mean that everything was perfect in his documentary, but it opened people’s eyes. So I was an adventurer in the beginning, meaning I was pushing my limits, doing like high mountains around the world and doing like more extreme sports. Then I got more into exploration, documenting, showing glaciers, doing scientific research, expeditions, doing the Northwest Passage, studying climate change, migration of birds. I started to get more into exploration to show people what needs to be shown. But that doesn’t do any change. I switched from exploration into philanthropy. How can I also do a change? Not only show the change but also do the change. So I started to work with organisations all over the world and represent them, work and travel with them and doing articles, movies. Everything from poaching of animals in Africa to poverty in India, to Bangladesh. I go around the world and I show places that needs to be fixed, changed or at least acknowledged, in some way. When I started to do those things like 15-20 years ago, it started more and more to make sense for me. Because before, climbing Mount Everest was a very personal thing. I wanted to climb this mountain. Me, me, me, me, myself and I. Very eager. Because it was important for me. I had the lowest score in gymnastics, so I wanted to show my friends, and myself that I could do it after the bet. But that doesn’t really change anything. When I started to show people how much garbage there is, they said: “Oh, that’s interesting, we want to hear about it. But then – okay then what? So what did you do about it?” – “Nothing.” – “Ah, boring. Next question.” – So then I started to go back again and clean up the mountain. I arranged the world’s biggest cleaning expedition. 200 people worked for three years to take down 15 tonnes of garbage.

My goodness. That’s a lot. What did you do with all this garbage…?

We thought, well, let’s give it to artists all over the world. So now we’re recycling Mount Everest by using and then recycling the garbage. Now that’s the only thing that I do for the last 15-20 years – focusing on change. You know, I’m not a scientist. I cannot show the figures. I’m not a politician. I cannot change the laws. But when I go to places where nobody else goes, I can show governments and people in wealthy nations what can be done and together we can make a change. And I think that’s our responsibility on this planet to make it a little bit better than when you came here in the first place.

But may I ask you, did you experience a specific moment or situation you can recall, where you felt for the first time something like: “Wow. That’s my mission!”

That moment was in Antarctica.

That was the moment when I felt that it’s not about me, it’s about what I see, about what I do. So one step was that, I can prove to myself, prove to others, that I can do things that other people might think is impossible. That’s number one. Number two, I actually understand that what I see, is important to other people. Number three was that, through me doing impossible things, maybe I could also help that other people might think it’s impossible. I went to Himalaya during the earthquake, for example. I was staying there for 2-3 months up in the mountains, raising money, building villages, building schools, monasteries, these kind of things. Because I felt that, those things were important that it makes a difference. This makes a difference for the world. By now, for me the word impossible doesn’t really exist. In nature, nothing is impossible. You see grass growing through concrete, you see people surviving cancer, you see like lots of things just with will, or with nature’s power, so in the universe nothing is impossible, everything is possible. Impossible just takes more time. So, with that philosophy, I’ve never given up because I always see that it is possible.

When exactly do you feel abundance in your daily life?

When I’m out in nature and I see how humans and nature and animals connect. You know, there’s a guy that I met recently at a conference, who started, through AI, to understand how animals are speaking and he’s trying to translate the sounds of the animals to actual words and things, through an AI that he has created. I mean, like the more and more I look into this world, the more and more I see that everything is connected. I spent 3000 nights in a tent, that’s eight and half years of my life and I truly see that everything is connected. The moment I really understood it, was my first trip to Himalaya. Because the philosophy of the Sherpa people, together with the animals, how they pray, when they eat an animal and how they take care of, everything together with nature it becomes like an ecological system of itself up there in the mountains.

What did nature teach you in all these nights out there in the tent?

When I’m out in nature and meet animals, I try to see them as energies and not just like an animal. I try to see them as a prolonged version of myself. That we want the same thing. So in nature when I’m sleeping, I’m trying to touch nature. Because, you know, on our shoes we always have a sole, so you’re walking with rubber on the ground, it’s like you’re touching something with gloves, or you’re sitting down with jeans or whatever. But I think it’s important to touch nature, because I think that nature gives you energy. When you do that, when you are in nature, and you sit in nature, you walk in nature, it’s just being connected in some strange way, that I cannot explain. Another thing that I always do a lot, I try to eat and drink from the same region where I am. If you take all these things together, connect them, then you know you get a more interesting energy of the food that you are eating, if they’re all connected from the same energy field. I’m not really sure about the exact moment when I started to feel this, but I do know that it’s always been in me. I just had to re-discover it. I don’t think it’s something that came up, I think it’s something that’s always been there. And I think that going back to the tribes and meeting the tribes all over the world, I think, that…that has changed me a lot. Because they have lived a life without us for tens of thousands of years, and it worked perfectly. So if we crash ourselves they will still be there. So when I go and visit tribes all over the world, I realise that they have zero interest in what we do and we have nothing to teach them, but they have lots of things to teach us.

What nature really taught me, and that’s why we live on the countryside, is that nature always aims to be in balance. Totally fascinating to see for me.

That’s why I just believe that all things are just a part of a big ecological system.

How can we re-connect with ourselves, with nature?

Well, I do think that it’s very important to have a connection to ourselves, but also to others, we need to hug, to touch each other, to touch earth, touch nature and to enjoy these vibrations. I think that we are so advanced in the technology, and we know so much. But we know nothing about the basic things. I mean, people are saying that: “I’m going to go out in nature.” Yeah, but we are in nature. It’s not until we realise that we are a part of nature, that we can live in balance with our ecological system. We have kind of speared ourselves in a kind of cocoon. We live in this high technology world, we have the latest iPhone which doesn’t really make any sense. It’s not important. What is important, for example is how we treat each other! I have been fortunate to meet with his holiness, the Dalai Lama a few times per year. I asked him: “How important is religion?”, because we were talking about fights between different religions. He said: “Johan, religion is not important. People can live without religion. People cannot live without love and compassion.”

It’s so important we try to do the best that we can. Just be a good person. Kindness is very underestimated. People believe in records. People ask me, like: “Oh did you climb this? How fast did you climb it?”, instead of asking: “Did you meet nice people on this mountain?” That is important to me and that is my memory. Another thing is that people are saying that all the biggest problem we have here, whether it is climate change or epidemics or COVID or poverty or cancer. All these things. No, it’s none of the above. The problem is us. Because without us, nature would not have all these problems. So, we wouldn’t have all these problems if we wouldn’t live the way we do. We have created most of these situations. So that’s why I think it’s very, very important to understand that we are the result of our actions. What we have done the last few 100 years, has resulted in the way that we are fighting problems today. I remember I was sitting next to this woman during a conference, she planted a few million trees in Africa. She won the Nobel Peace Prize. And I said: “Aren’t you afraid that humans will destroy nature?” And she looked at me: “Humans will never destroy nature, because well, when nature feels threatened, we’re out. It’s like don’t gamble with Mother Nature.” If we are seen as some kind of pest or some kind of problem we’re out in a second. We can never destroy anything, but we can destroy ourselves. And that would be very sad, because we are a very unique species.

I mean that’s why we talk about the force of nature, right? When we see how small we are when a storm is coming. We need to take care that humans are not only connected to their mobile phones.

Well, you see I think that is going to be a thing that is hard to take away. Because I think we stepped into new life where we are connected to the digital world. The question is more: how do we disconnect from the digital world?

I don’t think that we can live a life without a connection through the Internet. I think that we are far too involved. We cannot even book a ticket. We cannot even book a room. But: does my phone need to be besides me when I sleep? No. If I have lunch with you, why do I need my phone on the table? What is it that cannot wait? The moment when we start to realise that we can disconnect from it, that’s when we can live in balance. That’s why I’m so interested mixing top-notch technologies and the old wisdom of the tribes. How can we mix these things? How can we still keep the information that we had for tens of thousands of years? How to live in nature? How to use plants? How to use energies?

If I listen to your stories and what you just shared with me, is there anything you’re afraid of?

I’m afraid of Artificial Intelligence. I’m afraid that we are moving too fast. I’m afraid that we are giving the technical world its own choices to take decisions for us. You cannot show love through technology. You cannot show feelings through that. You can simulate them. You cannot create what Beethoven or Mozart created. You can create similar things. In 50 years in our lifetime, there will be no more tribes, which means that all of the knowledge, all of the things that we have been having for tens of thousands of years, are gone and we will never get it back again. You remember the fires in Alexandria, the library that burned down? Well that’s all gone. It’s like thousands of books, from Da Vinci or whoever, with information and wisdom, maybe philosophies, maybe mathematical studies, maybe evolutionary things in biology, astrology, all that is gone. So now we’re in the same position with the tribes. We can save them, or we can let them perish and be gone forever. The only way for us to survive our future is to go back and re-learn our past. We need to let nature find its way back to us. And I’m afraid also that in schools, they don’t teach kids how to collaborate and be creative together. Creativity is something that’s very important that technology cannot teach us.

What gives you wisdom in times of drama?

So when I was climbing my first mountain, Mount Denali in Alaska, I wanted to gather all the facts and information that I could have to climb this mountain. So I started to read all the books about how to climb the mountain, and I read about all the success stories. This guy climbed it in 21 days, this guy in 18 days. Yeah, but I want to know about the failures, where are the screw ups? So I started to study all the expeditions that didn’t make it. Somebody died, they got stuck in a storm, or they had the wrong gear, whatever. I started to interview old expeditions that never made it for half a year. And that became my greatest knowledge when climbing this mountain. Not that I knew what to do, but I knew what not to do, at least. So that was the most important thing. You can follow the same procedure for an organisation, a company or a relationship. So try to learn from other people’s mistakes because: that’s evolution. That’s the way nature works, and well, we are here today because of two billion screw ups! So I promised myself, I want to do as many mistakes as I possibly can in my life. Win and you win, lose – and you learn.

More information about Johan Ernst Nilson: #johanernst @ instagram